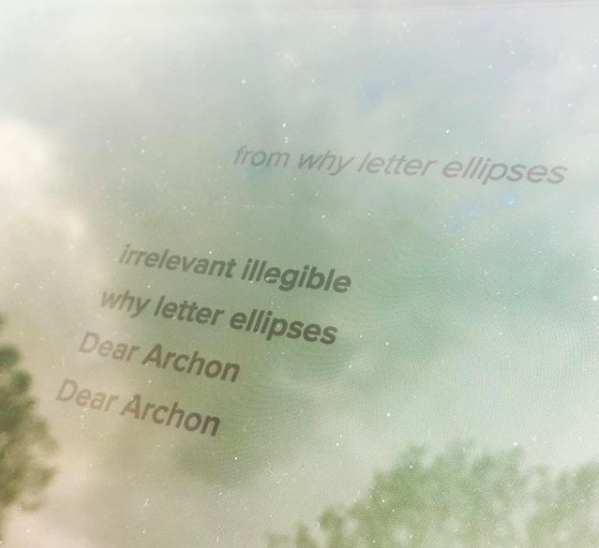

History is really an invitation

by way of arranged language

to read the occulted

in plain sight:

a poem.

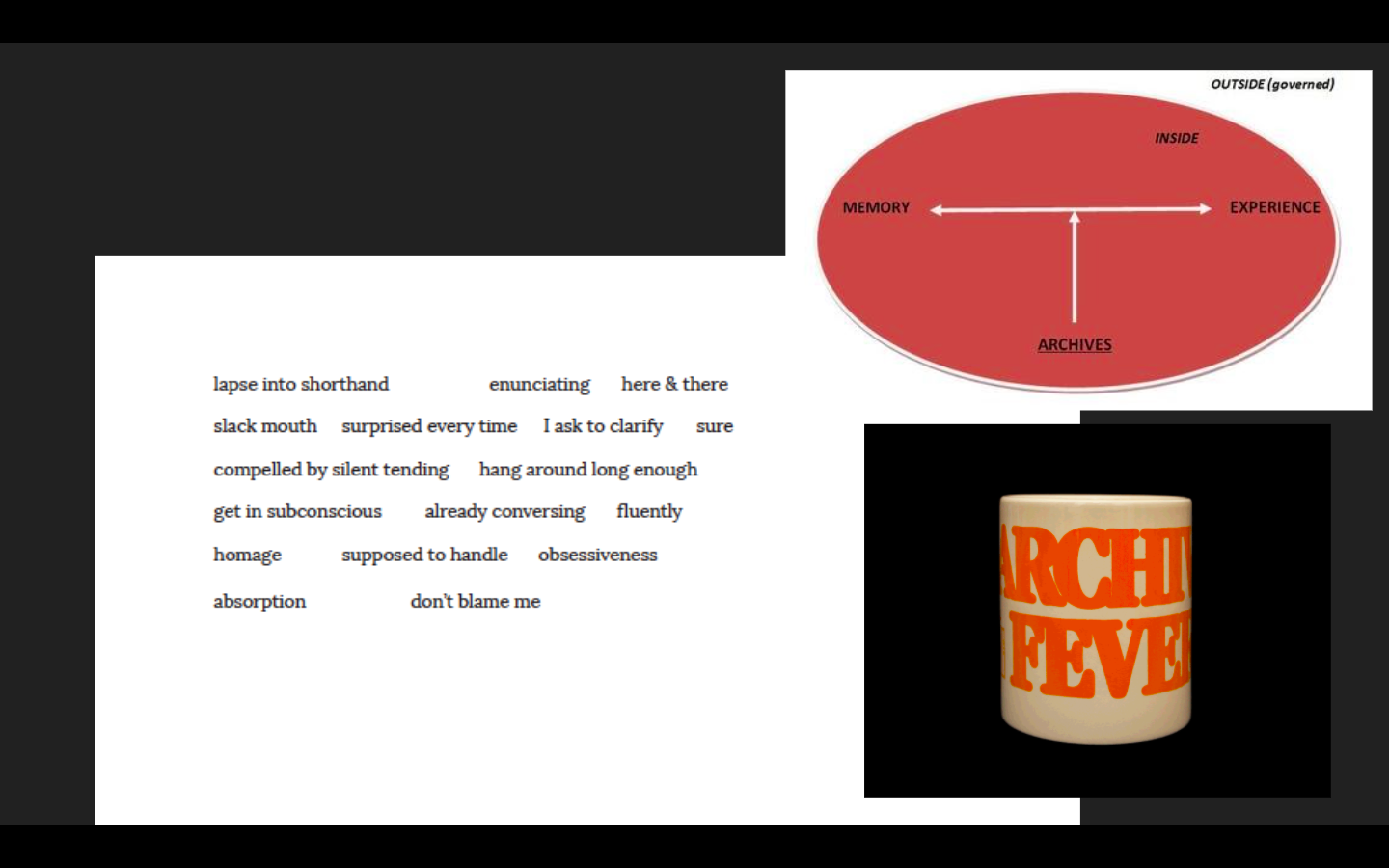

This book is a commingling of archives

with copious attributions

without peer review or a known market.

A history in which the document

is contemporary nonfiction

represented in verse

language’s contemporaneity taken back

from archive-as-Empire’s governance

and my poem journals are archival.

—from “CODA”

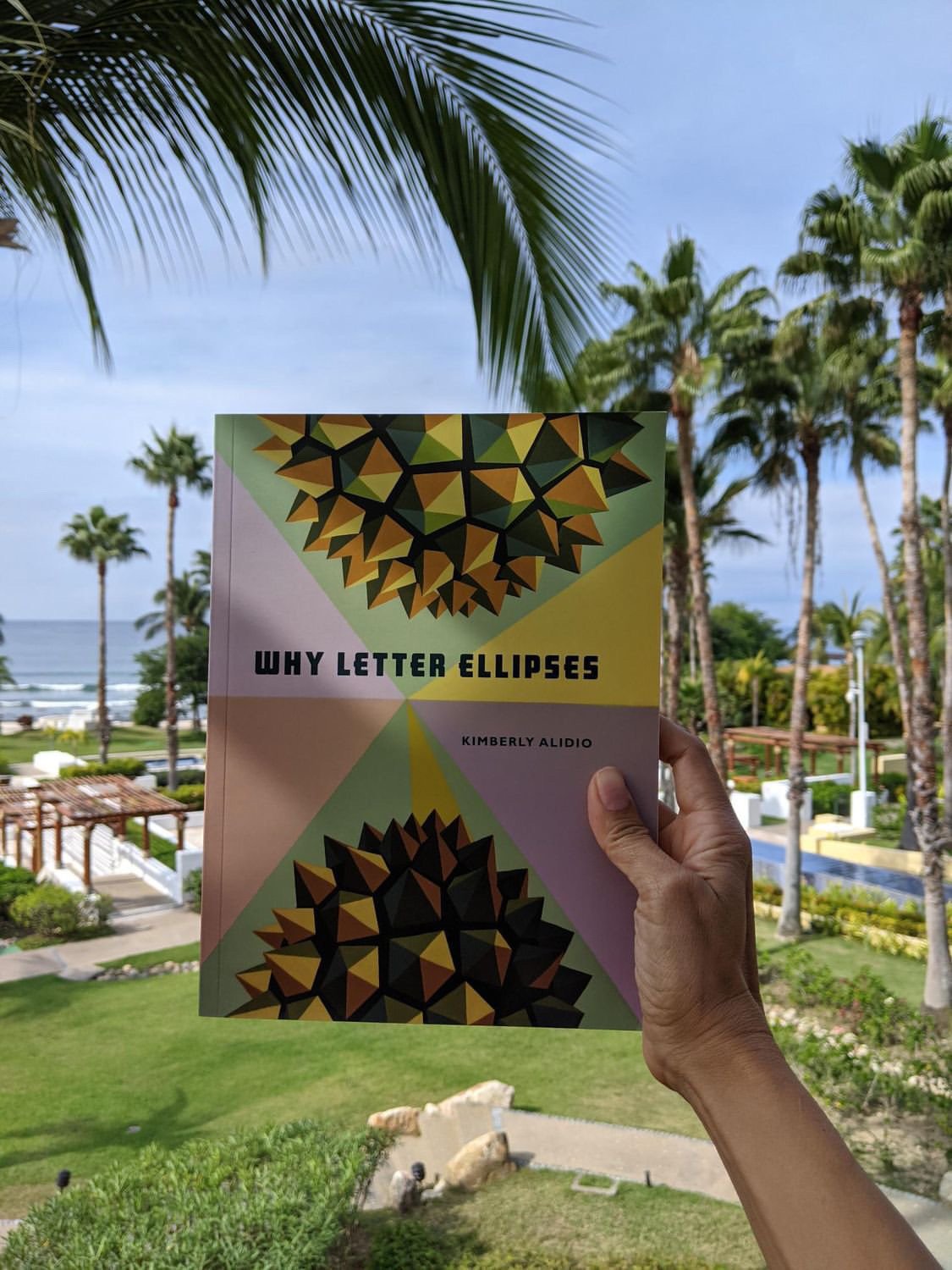

Praise

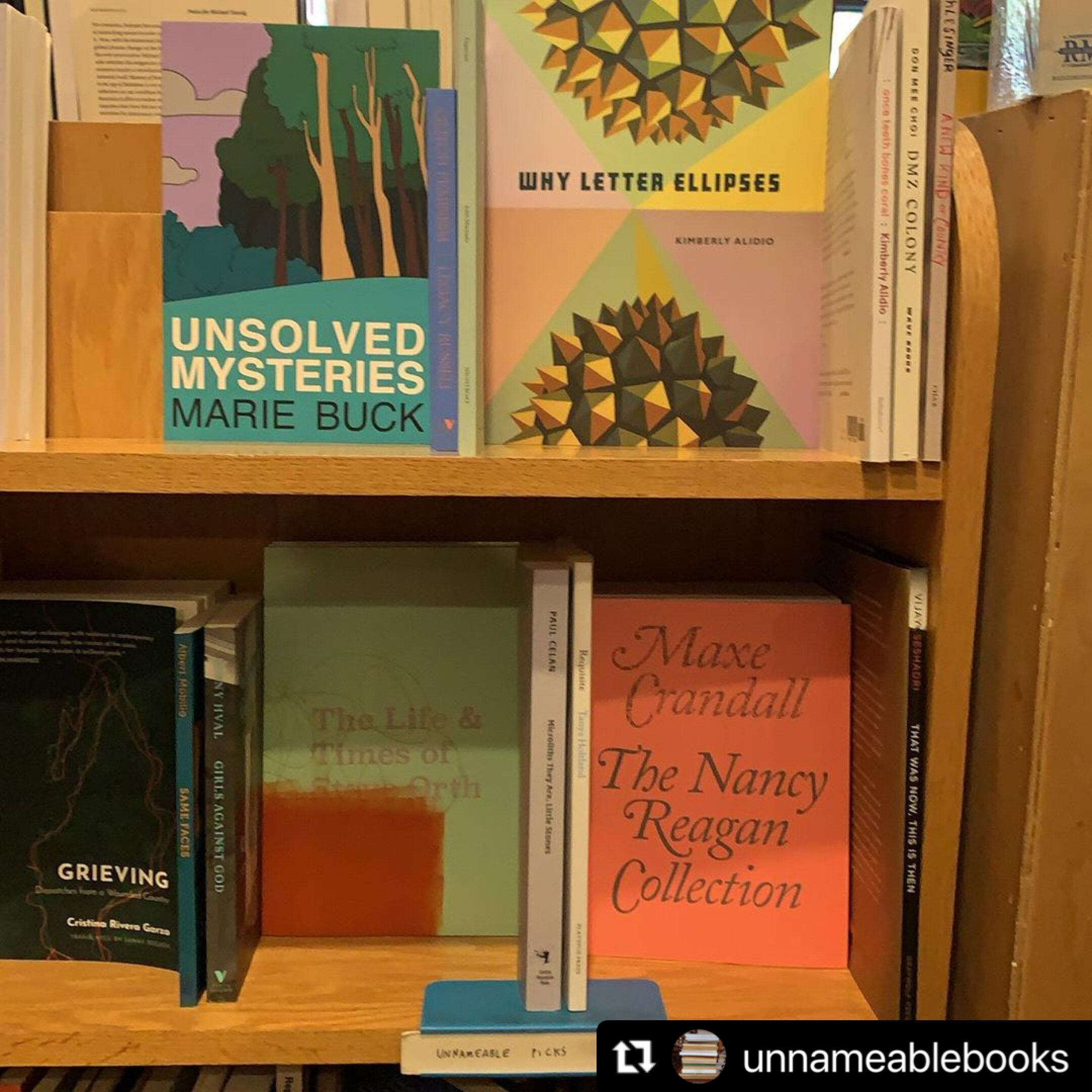

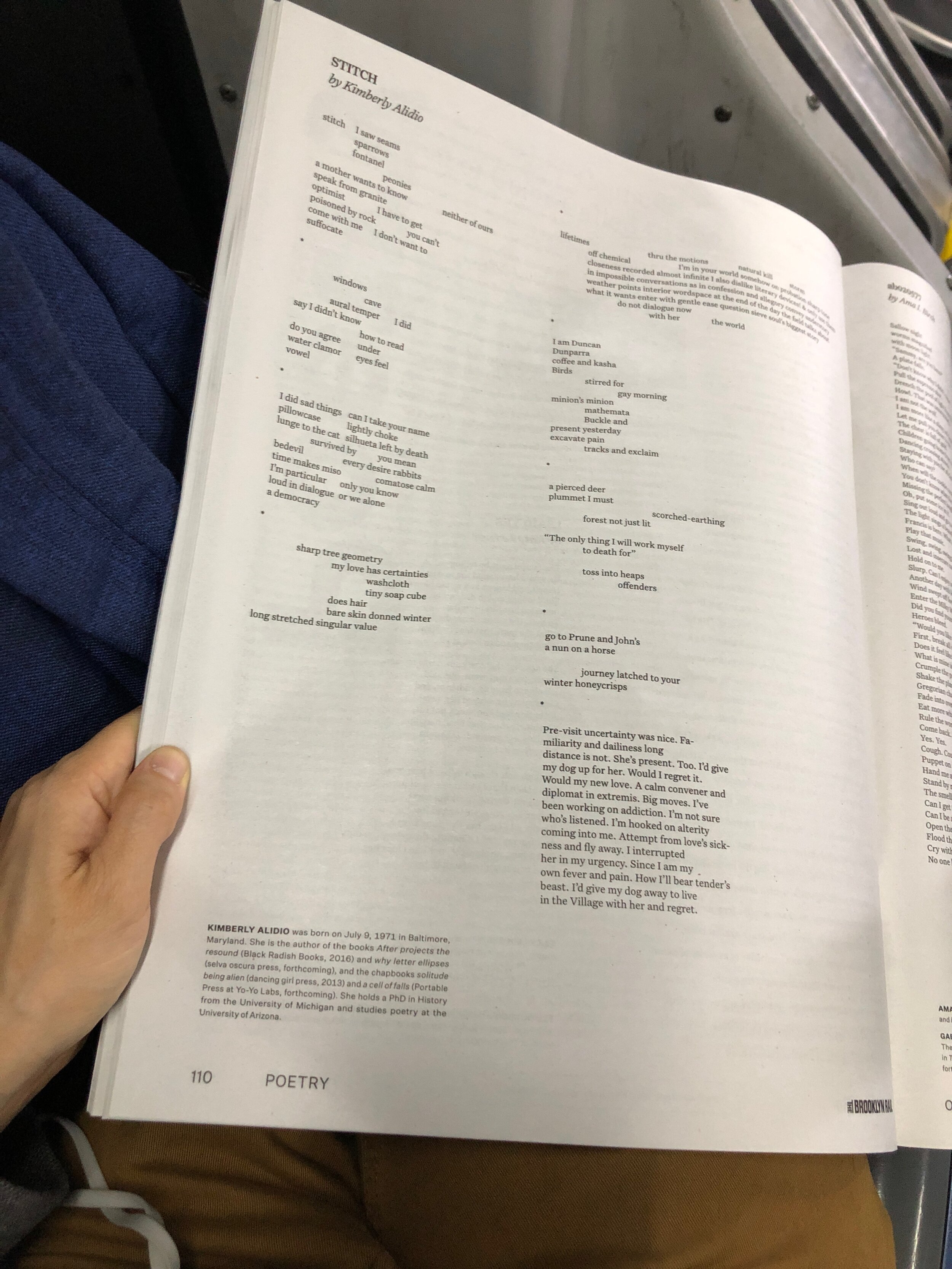

Kimberly Alidio’s striking why letter ellipses poses the deep challenge of how “to relearn how to exist in and beyond this world” through the poem’s archive, textual, and reading experience; particularly how to turn away from the poem’s sublime lyric to a material reality in the letter and the word and its deliberate omissions. Early on, in “stitch” do we get a confession about the poem’s intentions (a la edgy Marianne Moore): “I also dislike literary devices! & only use them in impossible conversations.” But it’s in these “impossible conversations” that proliferate in their glory throughout the collection that we see how the poet and the historian meet to bear witness of the world’s mercurial devices; its also how the literary devices manifest: “my cheek against tercets” grounding us in the utterances of both beauty and alterity. Alidio’s world is the one I need to step into daily. I'm so grateful for this book.

—Prageeta Sharma

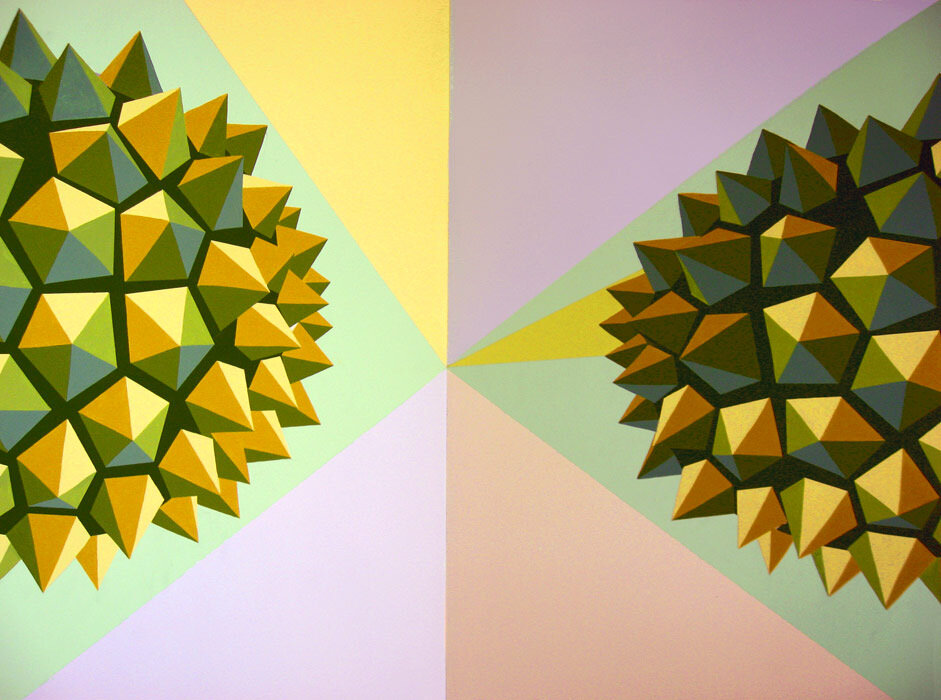

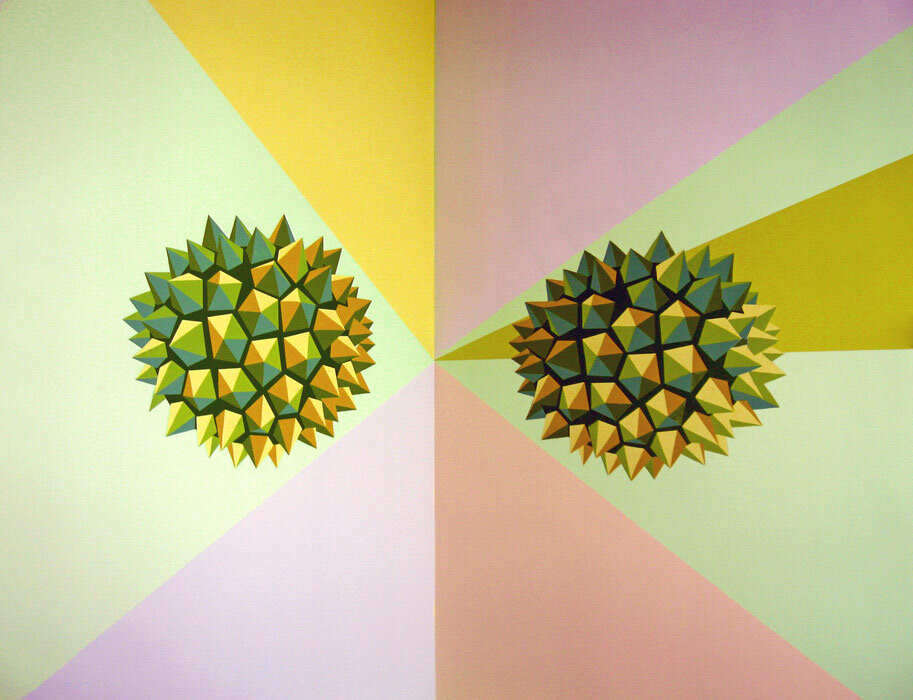

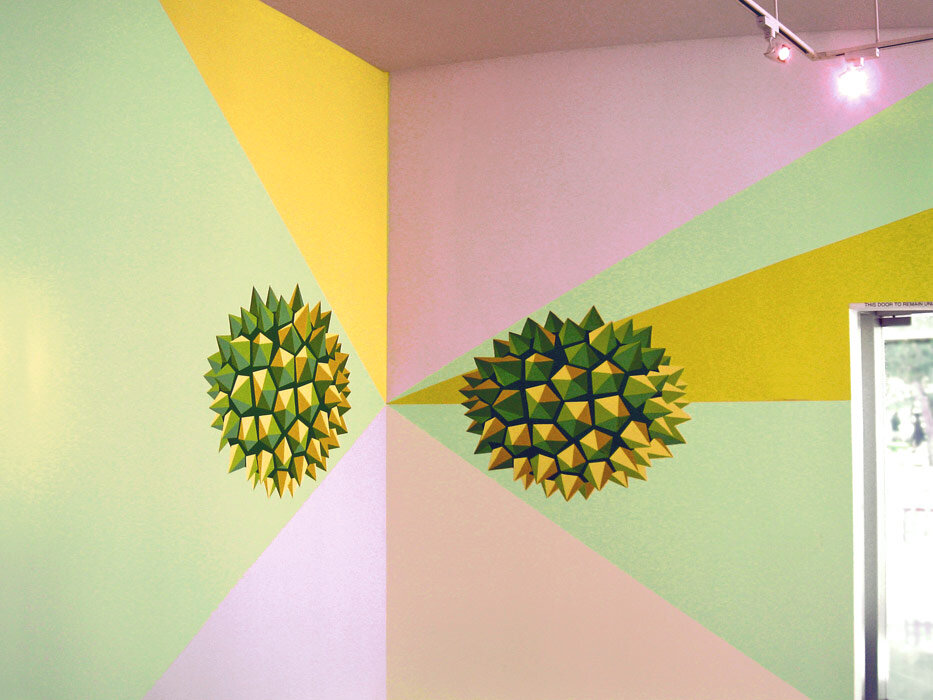

A voice — “a formerly pseudonymous avatar,” “your girl” — sometimes emerges from the insistently quotidian schist of Kimberly Alidio’s why letter ellipses. I think it’s this disembodied, omniscient, kind of scary voice (“who is shaking me/I cried”) that organizes the eye and ear to move through Alidio’s wordplay, a rough shuffle, nudging or sweeping words into a new kind of history writing that is both gentle and bitter. The poems’ many shapes, many ideas, many apparently random flourishes cluster around a rich sticky center that is a technique of accounting. Alidio’s accountability, then, forms something natural. A sunflower. No, a hive.

—Simone White

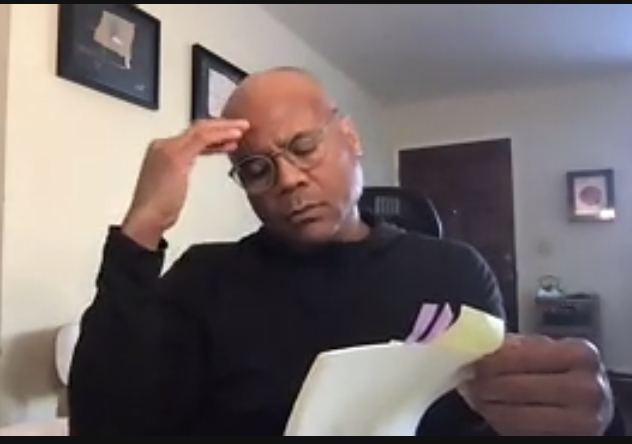

Book launch

Kimberly’s poetry constitutes a kind of counter-lyric scholarship. She’s a historian and her archival skills and resources are everywhere apparent in her work as a poet. For Kimberly, the archive is a zone of textual but also of textural information. And Kimberly mines in the interest of not only of revealing but also of making history. The making, the poesis of history is more emphatically and authentically Kimberly’s project than just about any other contemporary poet I know. The line from which Kimberly arrives and that Kimberly extends is Susan Howe’s and Layli Long Soldier’s and Myung Mi Kim’s and M. NourbeSe Philip’s. And that’s the highest compliment I can give. Like the work of these poets and as a function of their training in and critique of historiography, why letter ellipses constitutes what Kimberly calls a tousling of the archive. A shuffling and reinscription of pasts that are shared and stolen, obscured and ubiquitous. Kimberly’s language is always attuned to echoic of this complexity and I find that Kimberly’s work is the perfect expression and accompaniment of a deep, rigorously fabulant and fabulous archival turn. An ellipse that just won’t quit. —Fred Moten, Book launch event introduction

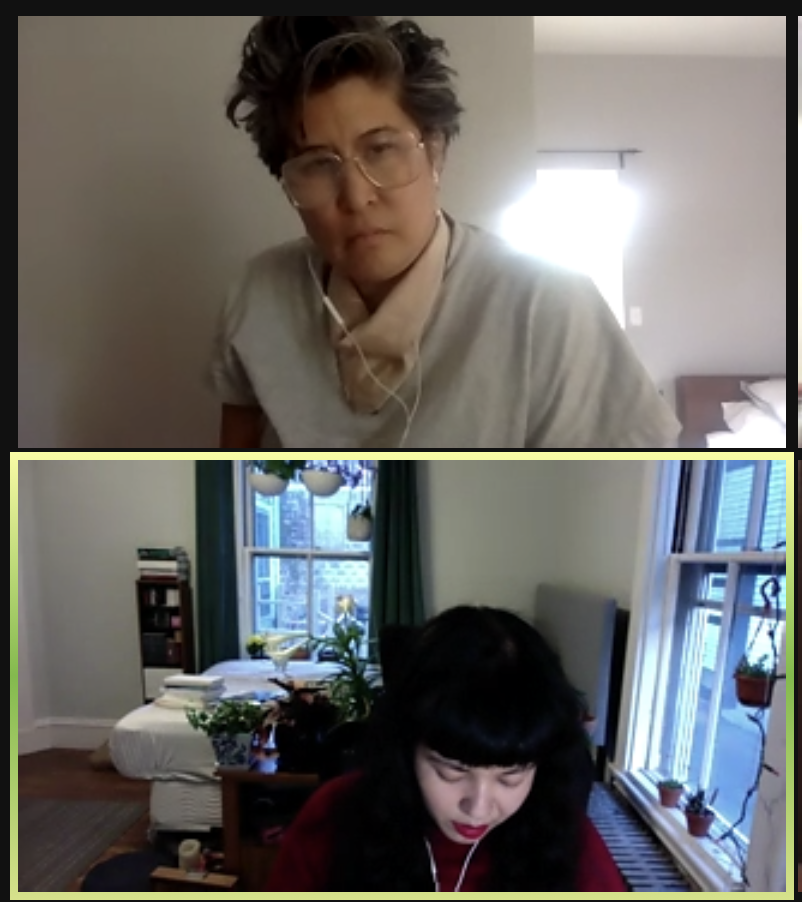

Book launch and discussion with Edgar Garcia, Jackie Wang, and Ronaldo Wilson, moderated by Fred Moten. April 14, 2021, New York University Performance Studies

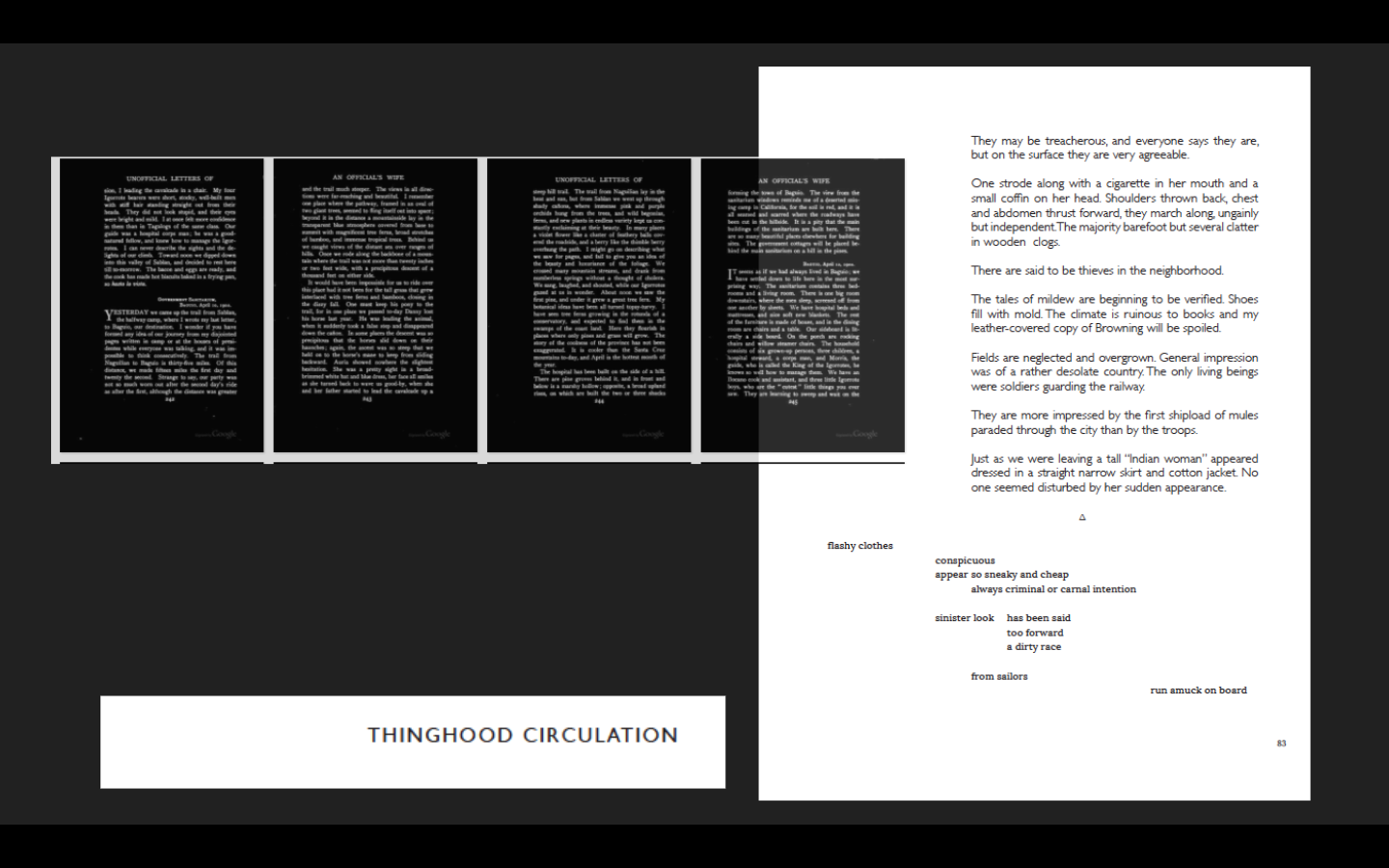

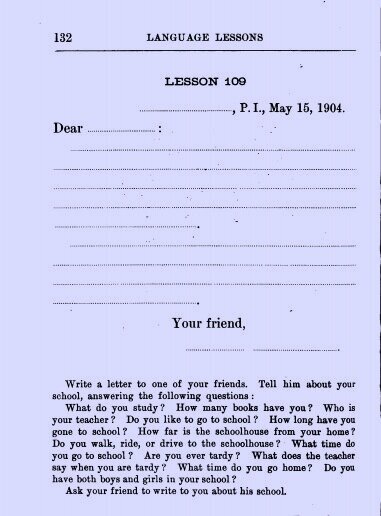

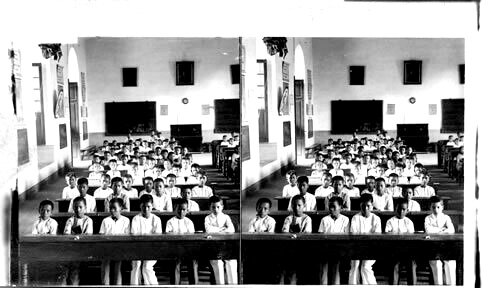

Jackie Wang: “You save the document from history … as occasional poetry, as inscription of the body. … Trying to save the document from history, trying to think of the document as inscription of the vernacular, a way of destroying the boundary between the dead and the living. I do have that aesthetic experience when encountering the document that Susan Howe is describing when she talks about the “telepathy of archives” and sensing through contact with the inscription the presence behind the inscription. And then seeing language as the medium of consciousness, as you put it in the Coda, and thinking about what it means to make contact with a consciousness now lost. That is what is potentially redeemable about the archive although I heed Saidiya Hartman’s concern with the violence of the archive and the way that it inscribes is contact between power and people subjected to violence.”

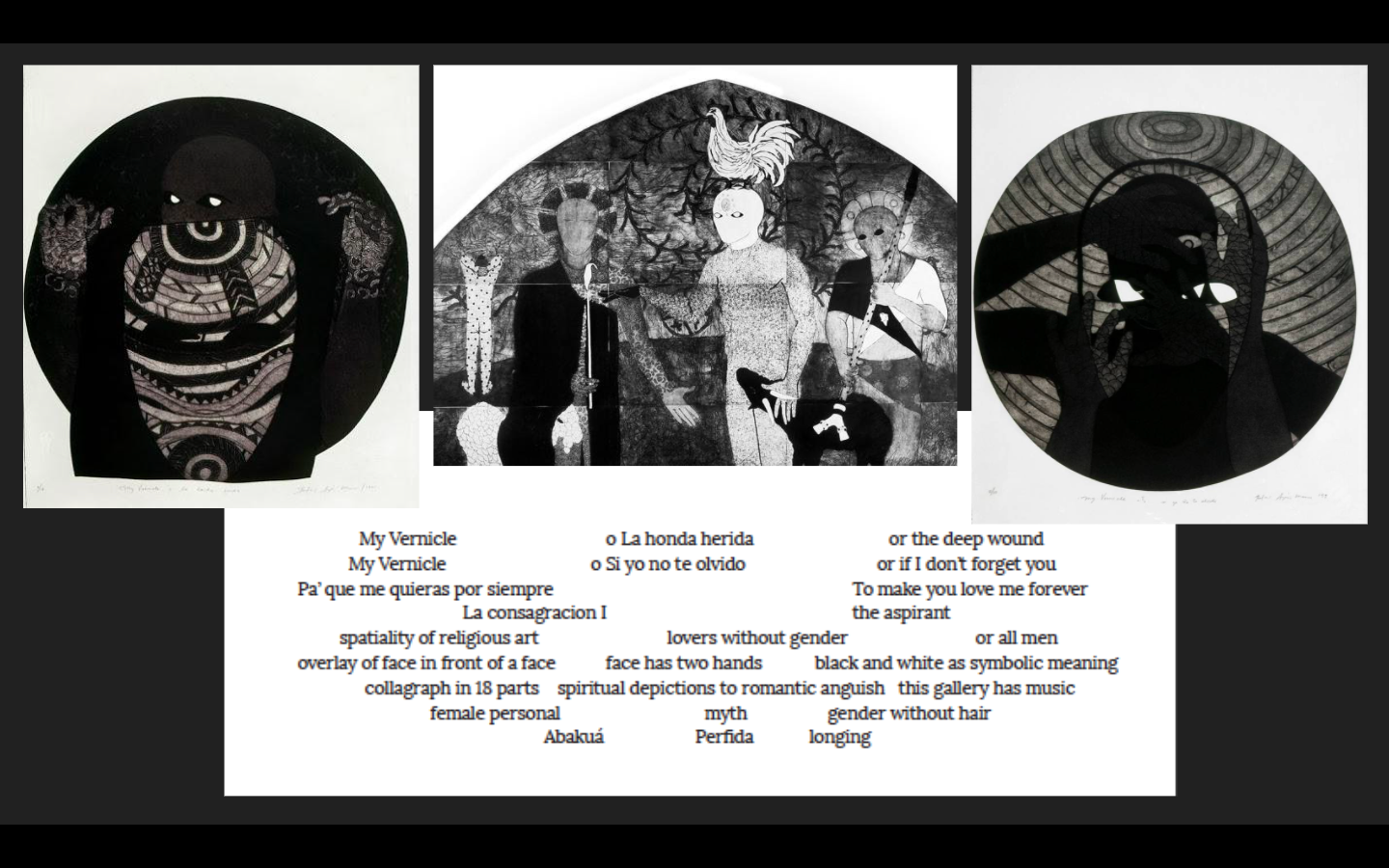

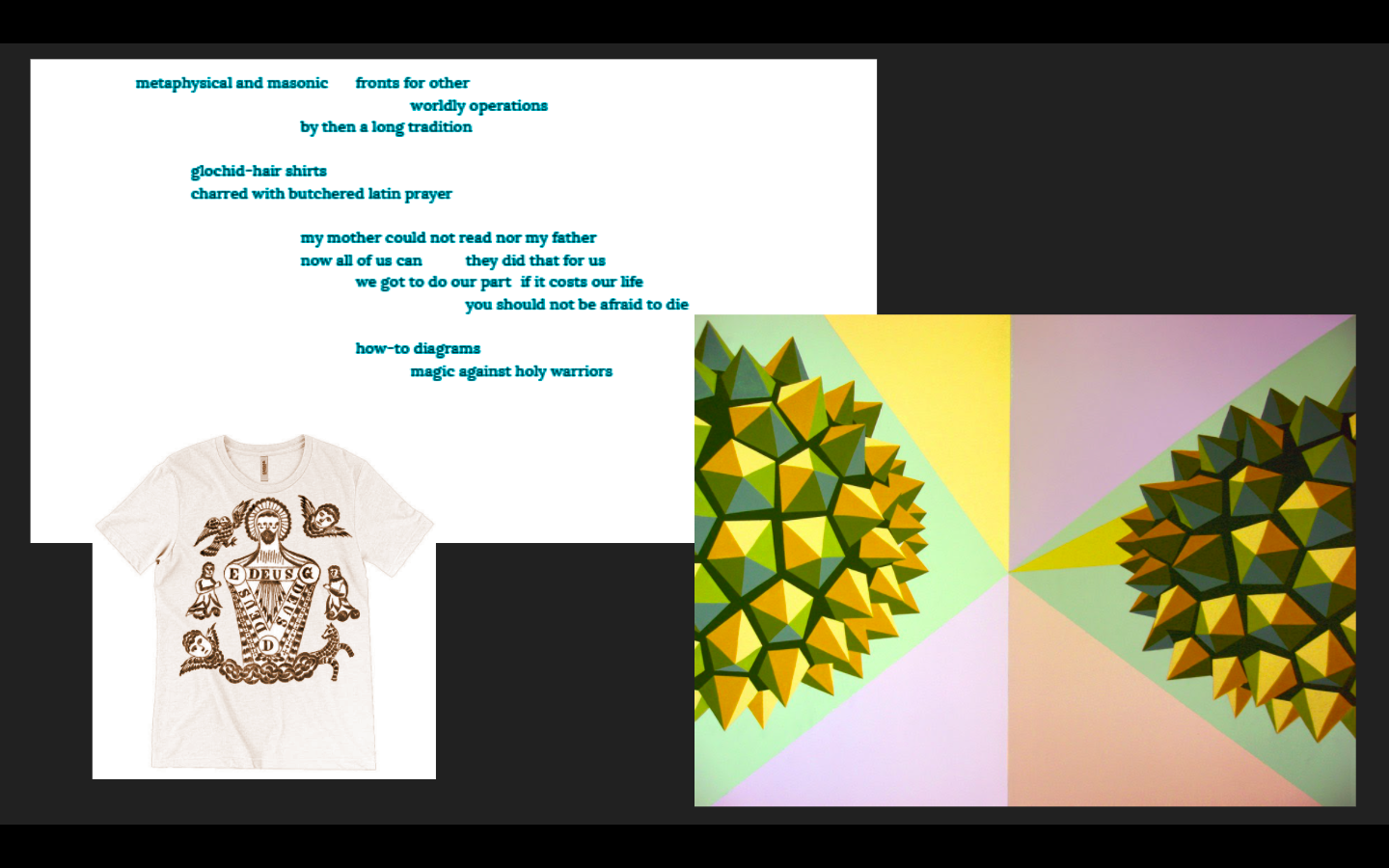

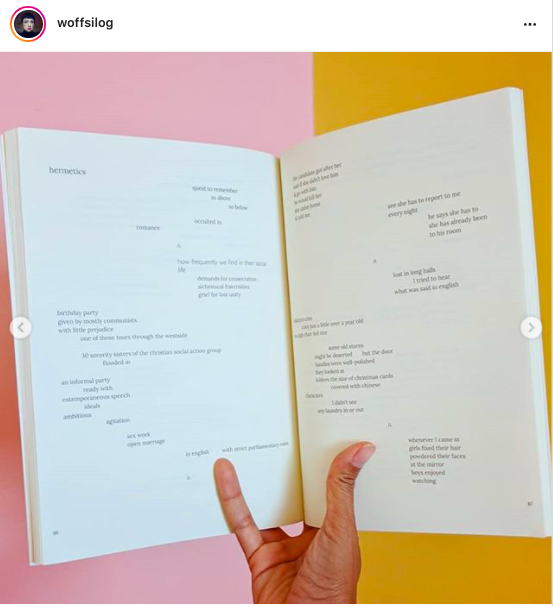

Edgar Garcia: “The Greek delta pyramids separating the poem shards in the long poem [“thinghood circulation’] have to do with the hermetic tradition, the shards of language that illuminate the whole. Hermeticism of course is a tradition of mystical thinking going back to Hermes Trismegistus but that was famously or infamously turned on its head by Walter Benjamin, who saw hermeticism and mystical thinking especially kabbalistic thinking as a way of thinking politically, thinking historically. And so I started thinking of each of these little shards as a kind of thought-picture of contemporary political, economic, and racial governance. All these shards can illuminate the whole, not because of any imagistic epiphany — all its realizations are in the texture of the language itself. With the intercutting of lyric and history in this book comes to accomplish for me is to position that illumination as a source of intellectual insight, beauty, intensity, joy amidst so much catastrophe.”

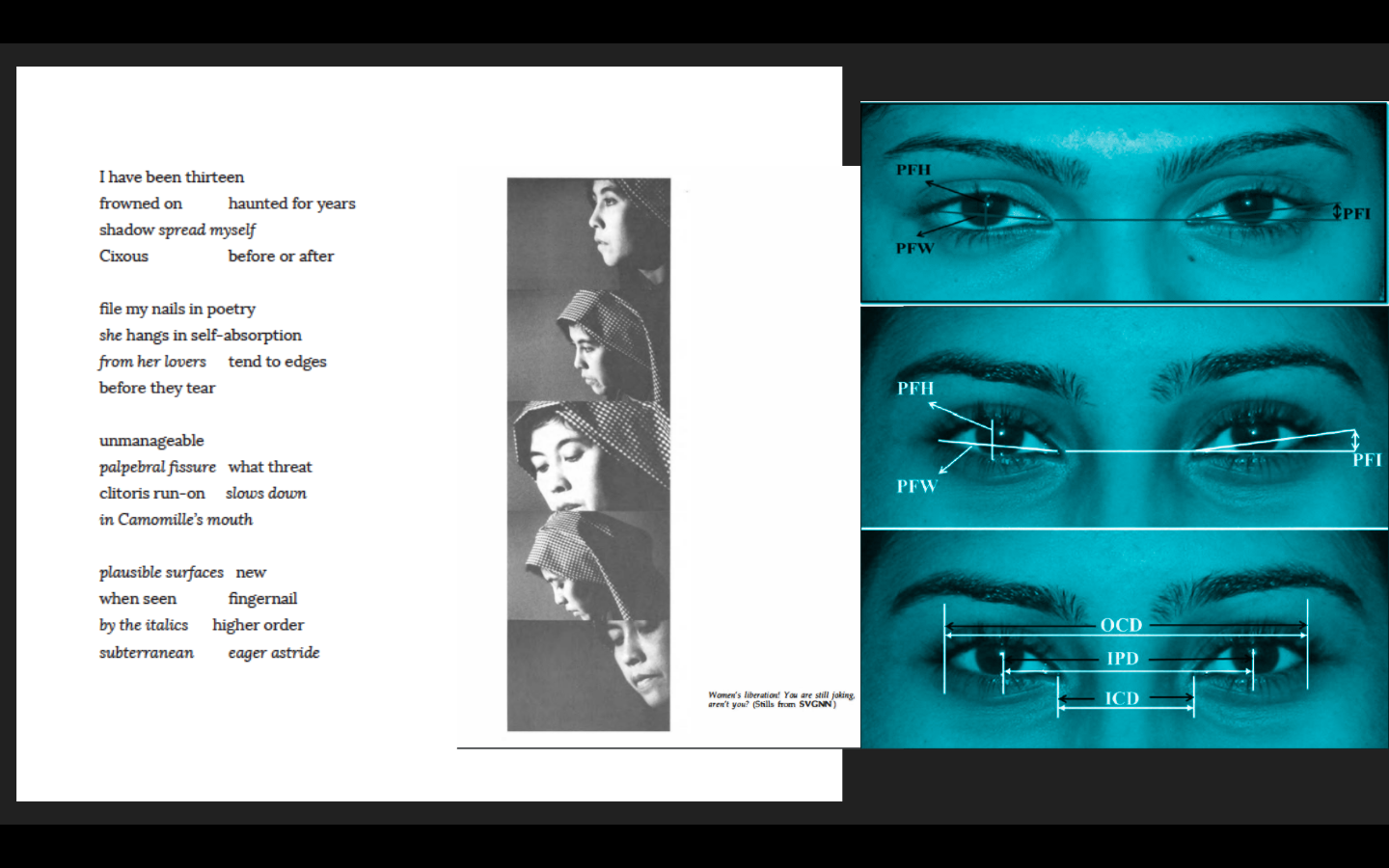

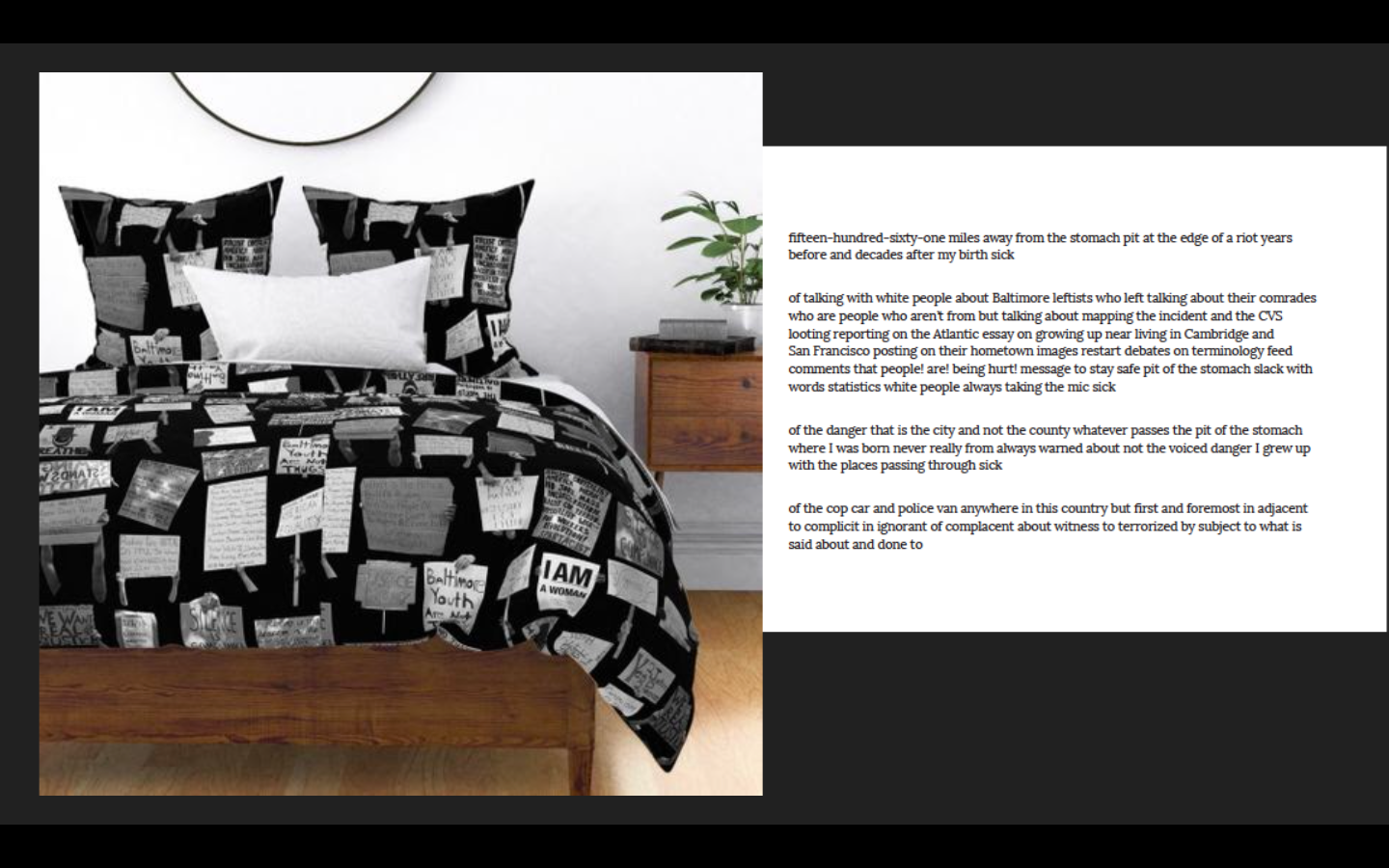

Ronaldo Wilson: “This book serves as both intervention and investigation. why letter ellipses inverts. It is, I am sure, not right to borrow from Freud here but Alidio uses the verb “invert” to pervert the realm of historical objectivity. To include the self and the self’s history insofar the case might be to get us back to the body. The palpable figure manifest through poem and coda, a decolonial, experimental, somatic poetics. We’re never alone. I’m interested in what it means to start in the space of this double-sided plant [“lodge plant material/ mechanical irritants”] and probably a double-sided feeling between conflict and tension, the ways in which the poem both relies upon and resists some bodies. Some body. But this double-helix inscription of some one thing’s desire helps me to further encounter Alidio’s why letter ellipses, a book I’m utterly moved by in its lack of exclusiveness. in including for those of us for whom otherness is a constant fact. But more idiosyncratically I’m moved in Alidio’s collection in its multiple counts of charging the field of the psychosexual, the political and historical, in very, very dirty ways. When I say “dirty,” I do not mean in ways that are sexually charged in order to be explicit vis-a-vis the arousal or perversity. I mean to say that the dirtiness is in the poetic manner that inhabits this collection, organized to let in the body too that inverts a queer torque.

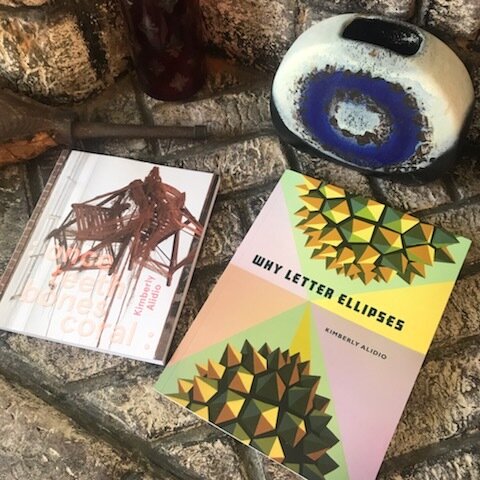

Kim’s Belladonna title, which I joke is the evil twin or the effete twin. Double books: one’s the brain, ones the lung, maybe they oscillate together — I’m not sure what’s happening between these two. But I had the pleasure of sitting with them both at the same time. Sitting in this Belladonna* book within a minefield of language, palpability person act desiring as figure, I was given some vectors through which to think about Alidio’s why letter ellipses. … Alidio offers “electromagnetichum” as one word scrunched up all together. Then: “without a passport/ I stopped showering/ you will smell me and come back/ drive.” I went to Luther Burbank High School in Sacramento, California, which was primarily Black folks, Filipino folks, brown folks. When someone in high school was funky, we might say, “you hummin’.” Which was an insult, capping on someone, but also invoking the familiar charge, however mean, one would say this to someone who’s a close friend. Maybe as a way to reel in and mark one’s mutual estrangement from manners, being clean or pure or white. You know what I mean. As a fellow traveler in the hum, her electromagnetic fortifications of the figure that urge your way back into history through compromise, through the other, national boundaries meet unrequited fear, possibility where the “archive is tousled.” Untidy. “I’m hooked on alterity coming into me” in the poem, “stitch.” Inverts the archive into the archon, where landscape absorbs alterity.

I admire the way Alidio tousles, dirties, and unmoors the archive as the other. What I love even more is how the book locates and unfurls desire as in “thinghood circulation” where the speaker cites Akilah Oliver “did investigate/ which is different than document/ remember and forget.” I’m always so moved to see Akilah. Alidio does investigate, exposing the dirty corners. In turn the alterity embodies us. Is this a work of collectivity? I think so. Is this a work of meandering? The hobby? How does one survive in the throat of the institution? What Fred is saying about Jackie’s work: what it means to be incarcerated in real time? All the time? “

Reviews + commentary + introductions

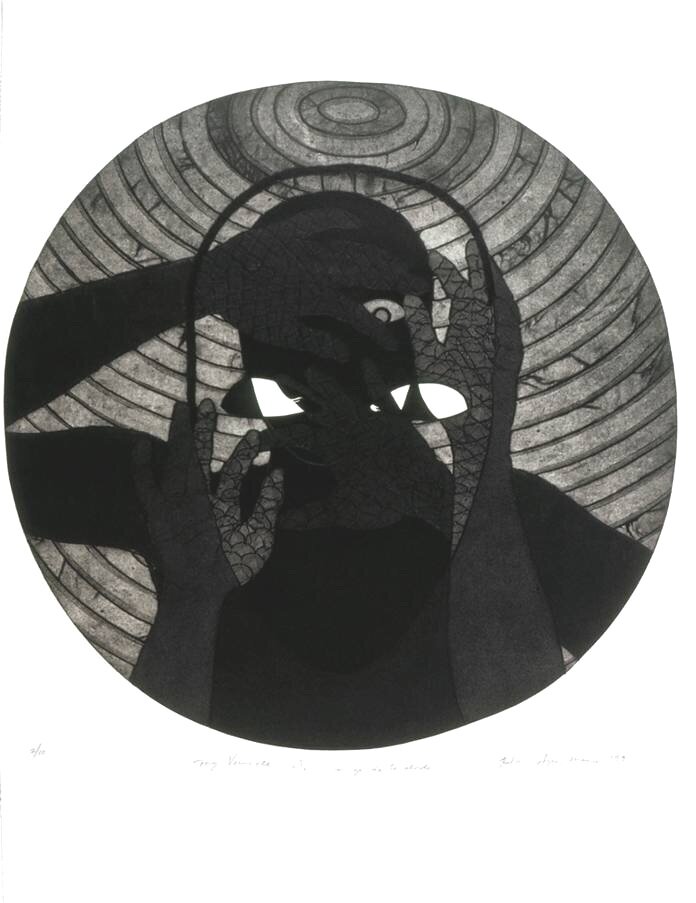

In contrasting the archive with letters between lovers, we’re asked to recognize the obvious fact that the archive is writing. But further, Alidio opens up the implications of the archive as a writing between people, people who collide through the chaotic intersections of doubts and desires, motives and intentions…. “I’ve stopped / being afraid,” Alidio writes, “under irrelevant / illegible light” (10). Unafraid because it is within this illegibility that a profound intimacy is made possible. We find that the eyes that see us most clearly are those that allow us to be more than what can be seen, and the arms that hold us best are those that embrace the ways in which we elude their grasp. But there’s a harsher side to this illegible light. History is written around the holes in its plot, around the gaps that omit the stories it does not or will not tell. Marginalized figures can seem confined within dim silhouettes that deny their presence and obscure the plain facts of their oppression. Several stretches of why letter ellipses cull from numerous sources, numerous voices, often through juxtapositions that feel more like collisions than static arrangements. Alidio’s sense of collage deliberately evades coherence and instead throws into relief how the power of validity is conferred upon some voices and withheld from others. —Morgan Võ [pdf]

I’ve read why letter ellipses again and again, sinking into the surround it conjures. I think often of how your work plays with sound as history and history as sound, how that exists as the erased voices that you pick up as with a microphone from the colonial archive of their absence. Your work brings intensely into focus that awareness, so often elided, that the imperial core is the periphery and that its “frontiers” determine its actual space, its domination by these conduits of extraction. I feel enveloped by sound and meaning when I experience your work. It reminds me of a concept that I learned from a Maryanne Amacher interview: “structure borne”—when you get the sound to travel through wood or stone or some other material. That seems like something your poetry seems particularly attuned to: using the poem as something that vibrates and amplifies through the material. —Geoffrey Olsen

The letters on these pages have teeth; safeguard the tips of your fingers.—Irene Suico Soriano

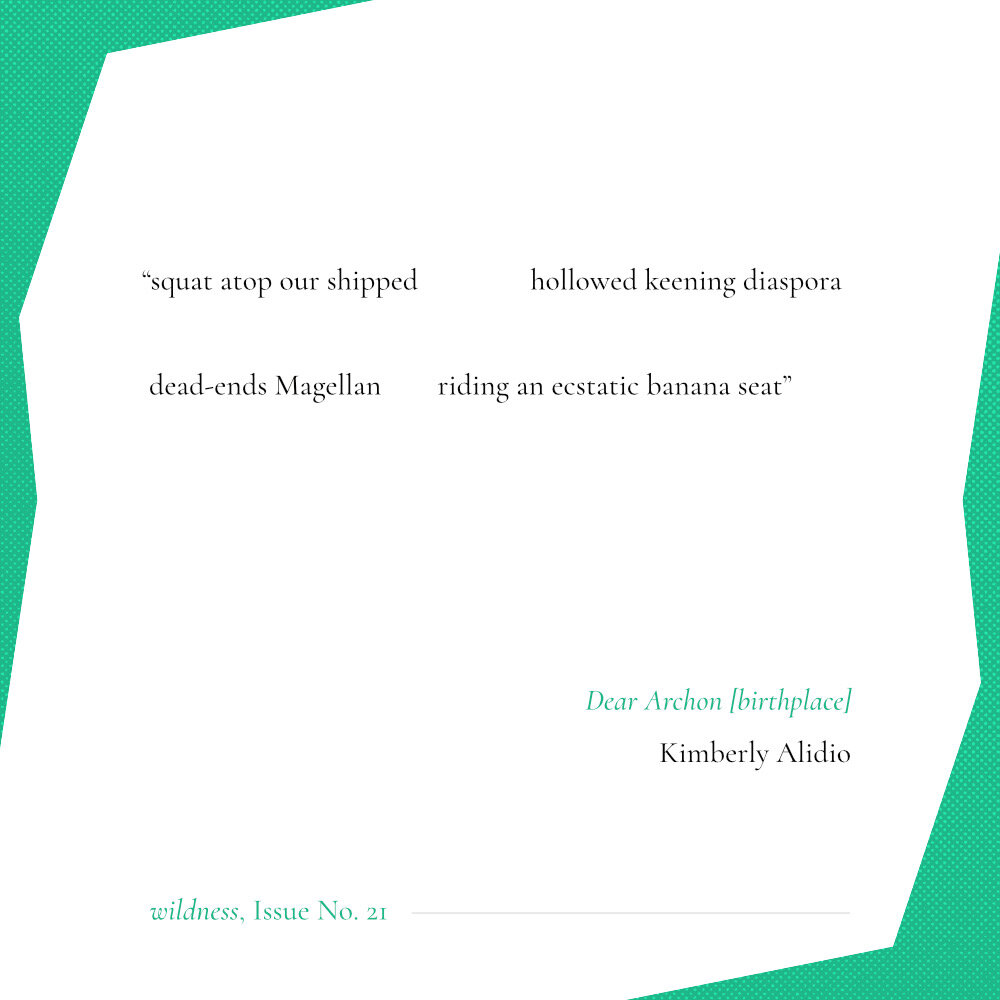

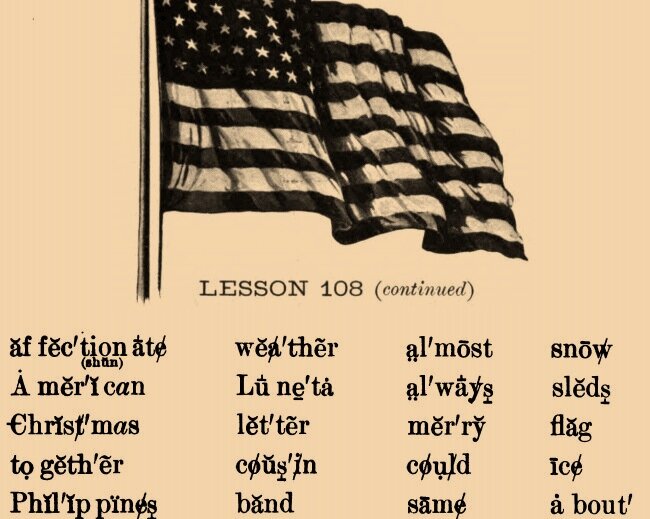

Alidio’s is a lyric less broken than stitched, structured as a kind of collage-lyric … informed by history and driven to, as she says, unsettle. Her poems are expansive, far-reaching and multiple, forming a pastiche of energy, language and sound. She writes the archive, and from the archive, as her extensive bibliography endnotes suggest, weaving in thoughts and phrases from writers such as John Dryden, Gerald Manley Hopkins, Stacy Szymaszek, Alice Notley, Amiri Baraka, Bernadette Mayer, Fred Moten and Edith Moses, as well as references from Filipino Pioneer and Filipino Student Bulletin. The poems exist as both a pulling apart and a gathering together. “Fragments her body into,” she writes, as part of the extended poem “a girl knows geopolitical strategy,” “someone historical existence / All actions [.]” —rob mclennan [pdf]

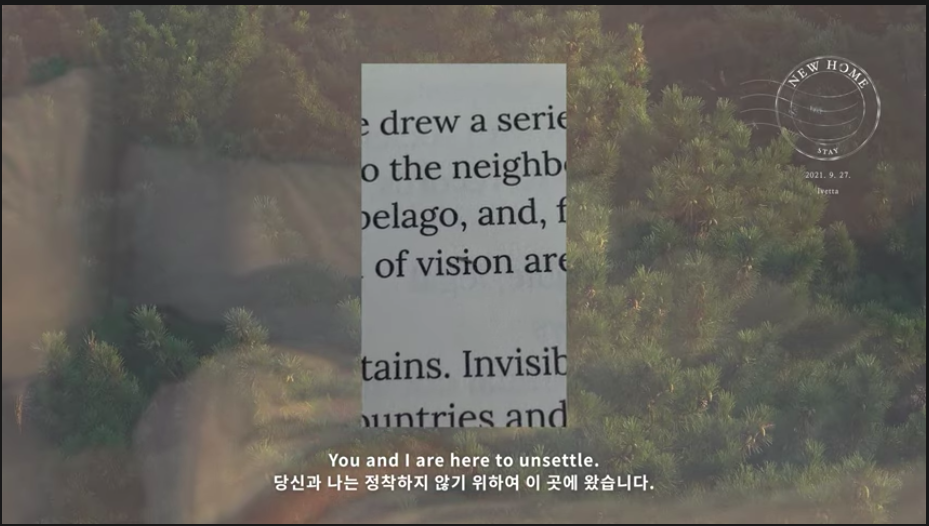

In line with such calls to reterritorialize the creative potential of a diasporic Filipinx subject, Kimberly Alidio’s why letter ellipses offers one lens with which to interpret the subjective relation to territory within a context of spatial construction…Alidio articulates a diasporic narrator who recognizes their ontological distance and attempts to surmount it in writing…[that] foregrounds an ontological aim “to unsettle” and to problematize the technologies of settling…thus point[ing] to how normativity functions as an inherent constraint for the diasporic subject’s interpretive task…[of] understanding the spaces they navigate as a form of archival practice….The speaker thus calls for bodies to be read—not as desiring machines or as an unmediated visual encounter, but a site from which affects begin to unfold the biopolitical contexts that “[y]ou and I are here to unsettle.”—Jon Joey D. Telebrico, “Poetic Assemblages: Filipinx Method on the Transpacific”

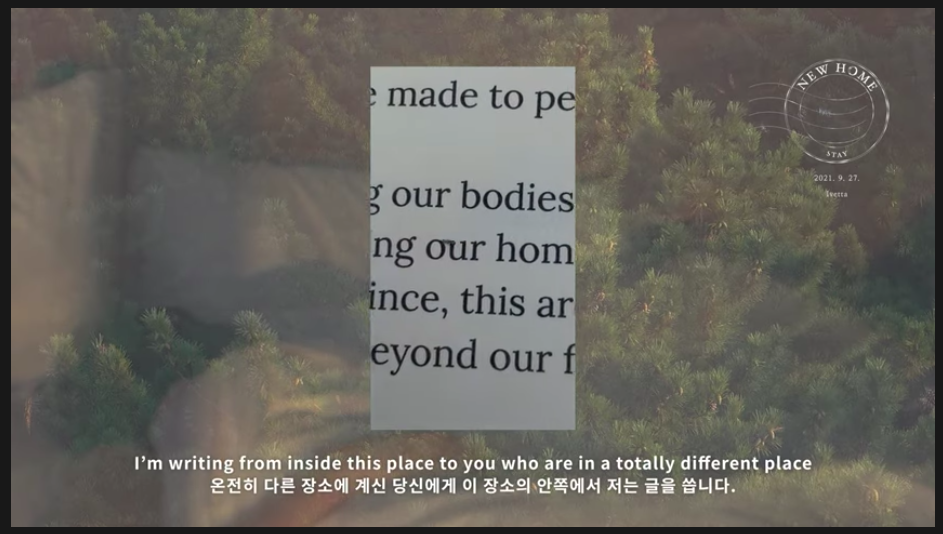

Last Spring, in a reading group, we read aloud Kimberly Alidio’s poem “dearest I’m writing from inside this place to you who are in a totally different place.” At the end, there was a collective flush exhale: it felt as if an expansive kernel of everything had been articulated and so what more was there to say, and yet in that articulation it enabled entirely new realms of what was possible to say. This is the alchemy of Kimberly Alidio’s work—their form of documentation of this world exceeds the constraints of the document, this world. They incisively track the contours and tangles of who’s comfort, whose home, whose sense of settledness is contingent on whose absented, de or unvalued, extracted labors of care while transforming this exploration anew and multidirectionally at the level of the letter, phrase, phoneme. The colonial and gendered forces of exploitation that undergird not only the archive (even the archive that supposedly exposes these hegemonic exploitations) but travel down to the gestural and enunciatory levels. “The bedsheet between us and the past has glory holes / Archive is a jail.” Their work forges new poetic maps that point us not to a singular location but toward the question “where do we place ourselves?” through a radical unsettling of language and belonging and towards the making of life under and beyond conditions of entrapment, suffused with a dyke eroticism. —Rebecca Teich, Introduction for Desperate Living Reading Series